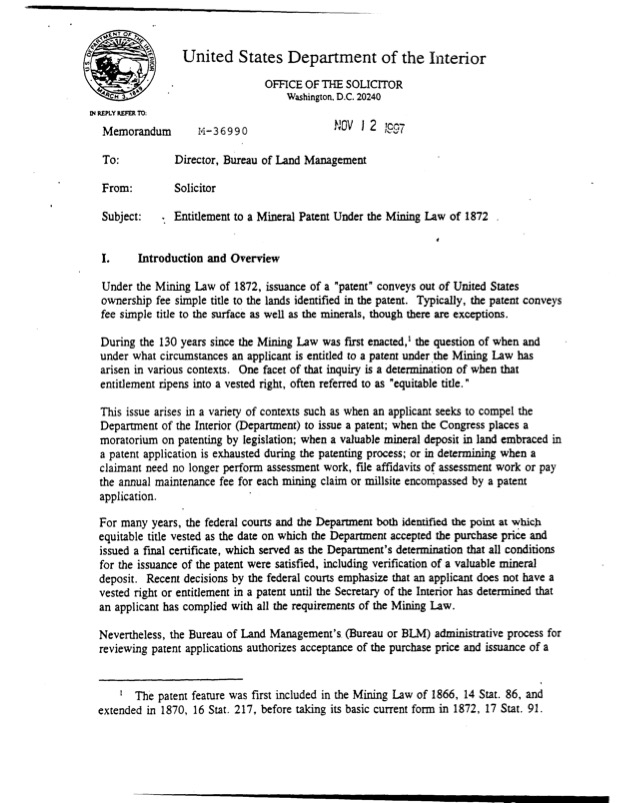

“U.S. Department of the Interior Memorandum M-36990, November 12 1997, Entitlement to a Mineral Patent.

Introduction and Overview

Under the Mining Law of 1872, issuance of a ‘patent’ conveys out of the United States ownership fee simple title to the lands identified in the patent. Typically, the patent conveys fee simple title to the surfaces well as the minerals, though there are exceptions.

During the 130 years since the Mining Law was first enacted, the question of when and under what circumstances an applicant is entitled to a patent under the Mining Law has arisen in various contexts. One facet of that inquiry is a determination of when that entitlement ripens into a vested right, often referred to as “equitable title.”

This issue arises in a variety of contexts such as when an applicant seeks to compel the Department of the Interior (Department) to issue a patent; when the Congress places a moratorium on attending by legislation; when a valuable mineral deposit in land is embraced in a patent application is exhausted during the patenting process; or in determining when a claimant need no longer perform assessment work, file affidavits of assessment work or pay the annual maintenance fee for each mining claim or mill site encompassed by a patent application.

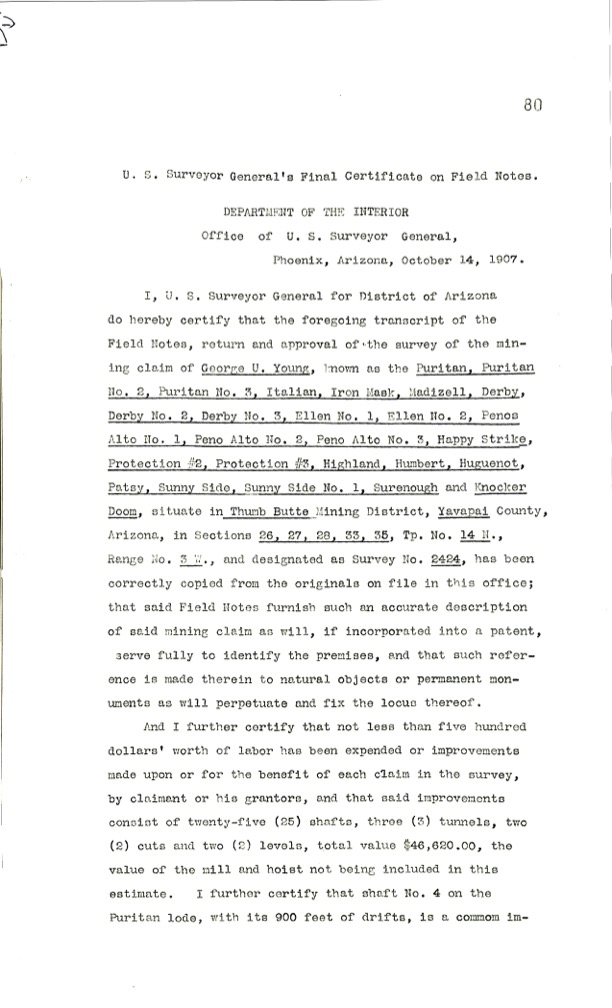

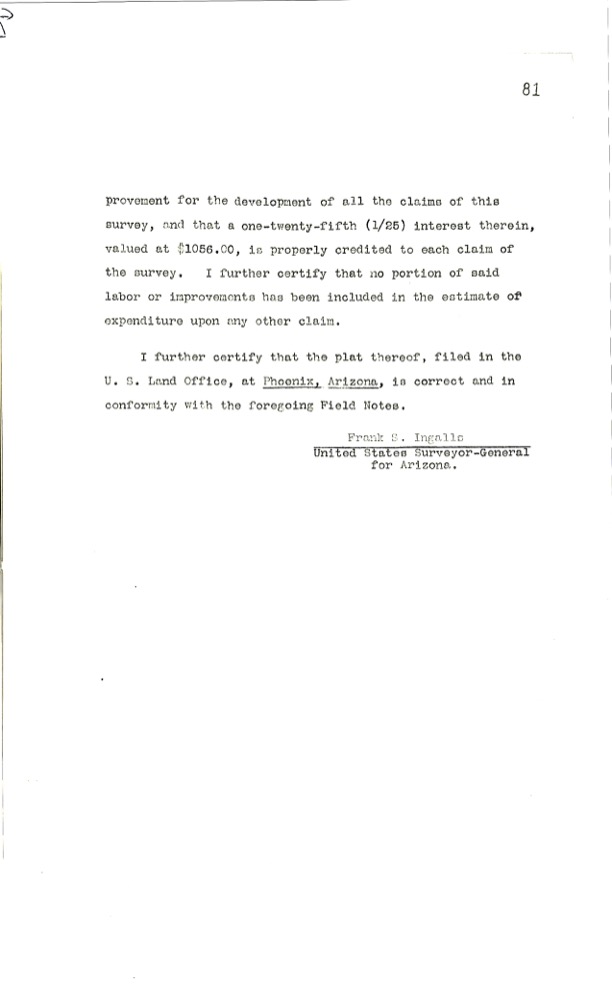

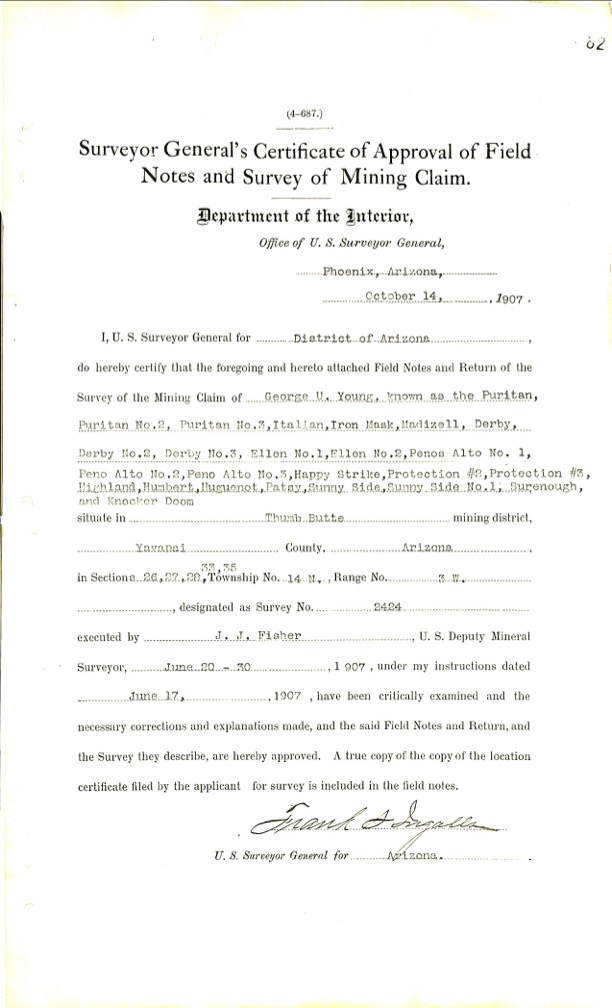

For many years, the federal courts and the Department both identified the point at which equitable title vested as the date on which the Department accepted the purchase price, and issued a final certificate, which served as the department’s determination that all conditions for the issuance of the patent were satisfied, including verification of a valuable mineral deposit. Recent decisions by the federal court emphasize that an applicant does not have a vested right or entitlement in a patent until the Secretary of the Interior has determined that an applicant has complied with all the requirements of the Mining Law. Nevertheless the Bureau of Land Management’s administrative process for reviewing patent applications authorizes acceptance of the purchase price and issuance of a *First Half-Mineral Entry Final Certificate* (FHFC) before the Secretary has completed his full review of the patents and confirmed the applicant’s compliance with the statute’s requirements. Thus, considerable litigation has arisen over whether and when an applicant as obtained a vested right in the mineral patent. Confusion has arisen in the legislative arena, as well, as Congress addresses proposals to amend the 1871 Mining Law.

This memorandum addresses this issue and recommends to the Bureau that it modify its mineral patent review process to more closely confirm to federal law.”

“Background: Patenting Under the General Mining Law

The Mining Law opens much of the “Valuable mineral deposits in lands belonging to the United States…to exploration and purchase, and the lands in which they are found to occupation and purchase…” 30 U.S.C. 22. It also provides the miner with the “exclusive right of possession of all the surface included within…(the) locations,” and the right to extract minerals. 30 U.S.C. 26, 29. ownership of a valid unpainted mining claim confers a possessory right in the land, but not fee title. A patented mining claim, on the other hand, results in fee title passing from the government to the claimant.

A claim may be located by “distinctly marking it on the ground so that its boundaries can be readily traced.” 30 U.S.C. 28 Discovering a valuable mineral deposit is a crucial step in the mining claim and mineral patent process. Although the Mining Law provides that “no location of a mining claim shall be made until a discovery of a Vein or Lode within the limits of the claim located,” 30 U.S.C. 23 the courts have allowed claimants to physically locate mining claim prior to discovery. See Union Oil Co. V. Smith , 249 U.S. 337, 347, (1919). However a discovery is vital to establishing the possessor rights attendant to a valid mining claim. Cameron V. United States 52 U.S. 450, 464 (1920) The same requirements apply equally to claims based on the discovery of a placer deposit. 30 U.S.C. 35 A patent may be obtained only “for any land claimed and located for valuable deposits” 30 U.S.C. 29

The Mining Law also permits the owner of a valid mining claim to appropriate non-mineral land as a dependent mill site.he statutory grant of non-mineral land for mill sites is expressly limited to land “used or occupied…for mining or milling purposes” 30 U.S.C. 42a like a valid mining claim, a valid mill site may be patented.

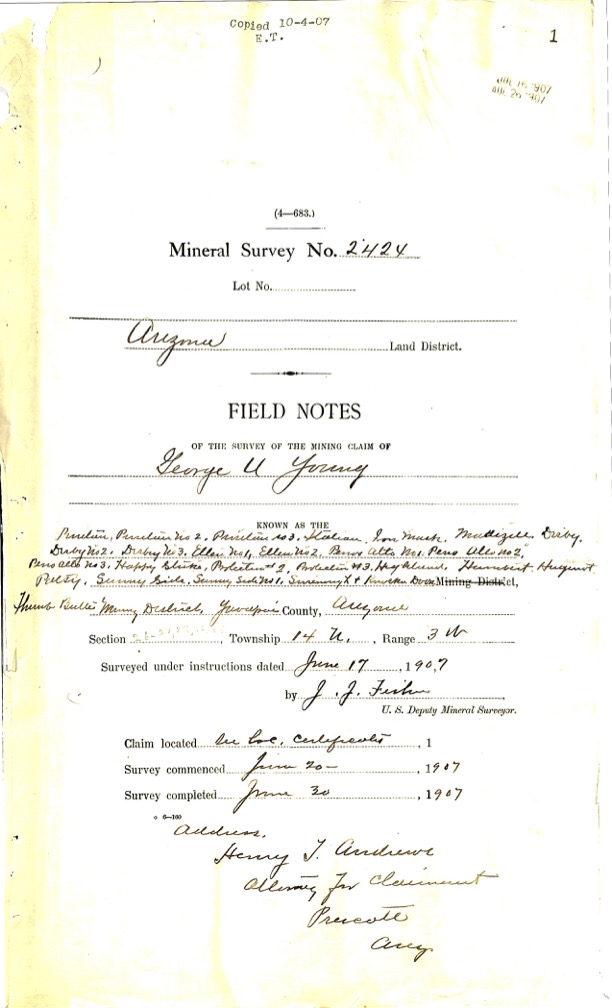

The basic requirements for securing patents are found in 30 U.S.C. 29-30, 35, 37 and 42. Section 29 sets out the “paper” requirements filing a patent application and receiving under current BLM practices, a FHFC. This section provides that a patent “may be obtained” by filing an application under oath showing such compliance” with the requirements of the Mining Law and complying with several other technical and procedural provisions. The applicant must include a survey of the claim, 30 U.S.C. 29, and post a copy of the survey and a notice of the patent application on the claim prior to filing the application. The applicant must then file a proof of the posting along with the patent application. A notice of the application must then be published in a newspaper nearest to the claim and must be posted in the General Land Office (now Bureau of Land Management office). The applicant also file a certificate that $500 worth of labor had been expended upon the claim and that the plat is correct, and must furnish an accurate description of the claim. At the end of the publication period, the applicant must file an affidavit showing that the plat and notice of application have been posted on the claim during the period of publication.

The Departments Current Mineral Patent Review Process

The filing of an application with the BLM commences the mineral patent process. BLM reviews the application to ensure that the applicant has complied with all the paperwork requirements of the Mining Law. If BLM concludes that the paperwork is complete, it requests payment of the patent purchase price. Upon receipt of the purchase money, the BLM state Director forwards the application, together with evidence of posting, publication, payment of the purchase price, and the FHFC, to the Regional Solicitor’s Office which provided legal services for BLM activities in that state. The Regional Solicitor conducts a legal review of the package, and then forwards it to the Solicitor for his concurrence in the issuance of the FHFC. The Solicitor then forwards the package to the BLM director for concurrence in issuance of the FHFC; he, in turn, passes it to the Assistant Secretary of Land and Minerals Management for further review and concurrence.

With the concurrence of these officials, the Secretary signs the FHFC. The FHFC is the Departments internal administrative recordation of an applicants compliance with the initial paperwork requirements of the Mining Law–i.e. that the title, proofs, posting requirements, and purchase money have been submitted to the BLM. The FHFC informs the applicant that the “patent may issue if all is found regular and upon demonstration and verification of a valid discovery of a valuable mineral deposit and subject to the reservations, exceptions and restrictions noted herein.” After the Secretary signs the FHFC, the patent is returned to BLM for verification that the applicant has made a valuable mineral discovery, or, in the case of a mill site, that the applicant is using and occupying five acres or less of non-mineral land for mining or milling purposes.”

“To that end, a certified BLM examiner completes a mineral examination of the claim or site and prepares a mineral report. BLM also considers other factors, including land status, reservations, conflicting property rights, and notifications to grazing pemittees, rights-of-way holders and state and local governments. The BLM examiner may also ask for additional documentation from the applicant if the initial proof of discovery does not provide BLM with enough data to make a determination. If the mineral report verifies the discovery of a valuable mineral deposit (or, in the case of a mill site, that the land is non-mineral), and BLM believes that all other statutory requirements have been met, BLM recommends that the Secretary sign the Second Half-Mineral Entry Final Certificate (SHFC) and issue the mineral patent.

With BLM’s recommendation, the patent follows a path similar to FHFC’s: review for legal sufficiency of the mineral report, the SHFC and the patent by the Associate Solicitor for Mineral Resources, and review and concurrence in issuance of the SHFC and the patently the Solicitor and the Assistant Secretary for Land and Minerals Management, before approval by the Secretary. The SHFC expressly provides that, once the form is signed, the lands are approved for patenting. Legal title to the land is transferred as of the date the Secretary signs the patent.

Until 1993, authority rested with BLM State Directors and District Managers to issue FHFC’s, SHFC’s and patents. That authority was revoked on March 3, 1993, by Secretary Babbitt. hereafter, the Secretary established the above-discussed procedures for Secretarial review before a patent could be issued. On December 6, 1996 the Secretary permanently reserved his authority for signing both final certificate documents and for issuing patents.

Federal Law Governing Mineral Patents

The Supreme Court has long acknowledged the central role of the Secretary in administering the public lands and resolving the rights of applicants to patent those lands.

4. Until 1958, BLM issued only one Final Certificate. Since 1958, however, BLM has split the Final “Certificate” into two parts: a first page and a second page, which were to be completed at different steps in the patent review process. In 1990 BLM, split the components into two wholly separate documents. Whether known as the “first page” of the final certificate or a separate document, the FHFC or it’s equivalent has signified only that the applicant had completed the preliminary paperwork requirements and had paid the purchase price.“

“More than a century ago, the Court described the Secretary’s role in the “important matters relating to…the issuing of patents” as “the supervising agent of the government to do justice to all claimants and preserve the rights of the people of the United States.” Knight v. Land Association, 142 U.S. 161,178 (1891) (pre-emption law case). The responsibility includes the “authority to review, reverse, amend, annul, or affirm all proceedings in the department having for their ultimate object to secure the alienation of any portion of the public lands, or the adjustment of private claims to lands, with a just regard to the rights of the public and of private parties.” Further, “the secretary is the guardian of the people of United States over the public lands. The obligations of his oath of office oblige him to see that the law is carried out, and that none of the public domain is wasted or is disposed of to a party not entitled to it.“Id at 181.

The Secretary’s general responsibility to examine the validity of a patent application applies with particular force with regard top mineral patents. Under the Mining Law, the Secretary is vested with the responsibility for “seeing that this authority is rightly exercised to the end that valid claims may be recognized, invalid ones eliminated, and the rights of the public preserved.” Cameron, 252 U.S. at 459-60. This is so because a “mining location which has not gone to patent is of no higher quality than are…unpatented claims….No right arises from an invalid claim of any kind. All must conform to the law under which they are initiated; otherwise they work an unlawful appropriation in derogation of the rights of the public.” Id.

The Secretary retains jurisdiction over mineral patent applications–and thus the power to determine the validity of rights claimed–until a patent issues and legal title is passed. Id. at 461, Ideal Basic Industries INc. V. Morton 542 F. 2d. 1364, 1368 (9th Cir. 1976) Until the issuance of a patent, therefore, “the United States which holds legal title to the lands, plainly can prescribe the procedure which any claimant must follow to acquire rights in the public sector.” Best V. Humboldt Placer Mining Co. 371 U.S. 374, 339 (1963)”