However rich Arizona mines have been, there is a suspicion that, before the days of copper, their net proceeds would hardly equal the amount of money furnished by ignorant investors toward the development of prospects that have never amounted to anything. Still worse, many of these enterprises have been obvious frauds, the money stolen from the unwary after advertising campaigns that claimed enormous riches for the mine that happened to serve as bait. Perpetuated by schemers, these campaigns often found their victims in the eastern states of the Union.

Today such work would hardly be done, for the United States authorities keep a close watch upon any extravagant advertising, and make investigations as to the basis of the claim.

One of the frauds in 1899 grew to such large proportions that Governor N.O. Murphy considered it his duty to issue a formal letter of warning, addressed to outside investors in Arizona mines. This letter brought down a storm of protest, and Murphy was accused of a jealous desire to ruin Arizona mining. Within a few months; however, it was demonstrated that his action had been dictated by a true sense of local patriotism. The particular swindle to which he referred to was the Spenazuma mining project, developed by “Doc” Flowers, who already had made an enormous fortune in the sale of proprietary medicines. The Spenazuma, which was exploited as the greatest mine in the world, was in Graham County and was a very ordinary mine indeed. Ore samples that were sent east and that were piled on the mine dump for the inspection of committees of stockholders were brought from other mines of far greater value in the Black Rock District.

The expose came through a newspaperman, George H. Smalley of Tucson, who furnished Governor Murphy with the information that led to the publicity. However, Flowers still sold stock, at advanced prices, even after his methods had been published in eastern journals. Flowers could not buy Smalley off and soon thereafter had to quit operations in the Southwest.

One amusing feature of Flowers’ operations on the Spenazuma was a fake stage hold-up, thoughtfully provided for the benefit of a number of prospective investors. He hired a number of cowboys to hold up the caravan of coaches, but the defenders succeeded in driving off the bandits. However, later, these “cowboy bandits” couldn’t keep from joyously telling their tale of “banditry.” Flowers was a man of true Wallingford stripe and found an opportunity for making money on every corner. In 1890, while under indictment on a charge of selling fraudulent stock, and while under bond for $50,000, he promoted to Philadelphia investors a company that claimed to have found a method of making gold. He was arrested on several charges of grand larceny, but he succeeded in escaping to Canada. Slow-footed justice, at last, came to him, as late as December 1914. After extradition from Canada, he went on trial in the east and at the age of 70, was sentenced to two years in the penitentiary. If he had stolen a pie his sentence would, probably, have been at least five years.

In 1892, Dr. H. H. Warner of Rochester, New York, an individual famed for his observatory, his bitters and his pills, bought of John Lawler and Judge Ed Avells, the Hillside group of mines in southwestern Yavapai County, paying $50.000 cash on the price of $450 000. The company then sold stock under the name of the Seven Stars Gold Mining Company. Ordinary stock was sold at $1 a share, but beyond this, was also issued a block of 100,000 shares at $5, on which Warner, then believed to be worth millions, personally guaranteed annual dividends at 13%. Warner failed soon afterward and the mine, with much-added development, went back to the sellers, despite the protests of the stockholders.

In clearing up the affairs of the George A. Treadwell Milling Company, which had a reduction plant near Humboldt; it was claimed by stockholders that the promoters of the company on stock sales aggregating about $1,000,000 had cleared up a “profit” of $500,000, while not more than $100,000 had been spent on the property. One of the promoters, a New York lawyer, was said to have been paid counsel ‘s fees of $36,000.

One Eastern firm of brokers secured bonds or options on a number of Yavapai County mines, of the “has-been” class, of former leaders in the silver production of Arizona. These old mine workings were cleaned out to an extent, and some of the cleverest of advertising, mainly beautifully printed circulars and letters, were sent to potential investors.

Though describing plans of reduction works that would make rich the miners of the entire country, little was done after the stock-selling campaigns. With a stock seller, it mattered little whether his mine had any worth or not. He never did more mining than was necessary to make a showing for his campaign. This condition was not peculiar to Arizona. Such schemes were worked much more generally, and with even greater success to the promoters, during the days of mining activity in Alaska and Nevada.

One individual who had a mine near Prescott issued a unique prospectus full of quotations from the Bible and of glittering generalities concerning the wealth that was to be secured in the marvelous mine exploited, which later seems to have dropped from the public eye. Within the prospectus appeared the following:

Come, little brother, and sit on my knee,

And both of us wealthy will grow, you see;

If you will invest your dollars with me,

I will show you where money grows on the tree.

Early in 1899, there was excitement along the Grand Canyon where had been staked a large area of lime-carbonate capping, thought to have been valuable for platinum. The bubble was punctured by Professor W.P. Blake, Director of Mines of the Territorial University, who after careful assays reported that the “ore” sent him was a carbonate, containing only silica, calcium, magnesia, iron, and a little alumina. Not a trace of platinum could be found, though similar rock elsewhere submitted was reported to have returned values of $300 a ton in platinum. While deploring the influence of his report upon the prospectors who thought they had found wealth, he said, “the people of Arizona generally do not propose to profit by ignorance, pretense or misrepresentation.” It is probable that the excitement all started through efforts made to assure trail holdings down into Cataract Canon.

Another notable swindle was that of the Two Queens and Mansfield Mining companies. The former had several prospects, near Winkelman, about 100 miles southeast of Phoenix. The latter had a mine in the Patagonia District of Santa Cruz County. The Post Office department secured the arrest of several Kansas City, Missouri stockbrokers, who had been selling shares in the two companies, by means of extravagant full-page advertising. As is usual in such cases, strong defense was made on the basis of testimony taken in Arizona, but the defendants finally were convicted and were sent to jail in May 1909, though, as usual in such cases, they received relatively light sentences.

Another typical instance concerned a temporary resident of Wickenburg, Arizona, who had bought a mining claim a few miles from town. He sold at least $100,000 worth of stock in several villages along the Hudson, near West Point, and, in order to show his good faith, brought out a Pullman carload of selected stockholders to view the wonderful mine from which he was to make them fortunes. After showing the potential investors the mine, the stock was quickly sold and the men returned the east. The following day, Sheriff Hayden of Maricopa County appeared on the same ground with an attorney and formally sold, under a judgment of debt, all the property owned by the promoter or his company in that vicinity. Hayden afterward was filled with regret that he had permitted the attorney to delay him one day on the sale, or he would have been on the ground at the same time as the investors’ party.

The Great Diamond Swindle

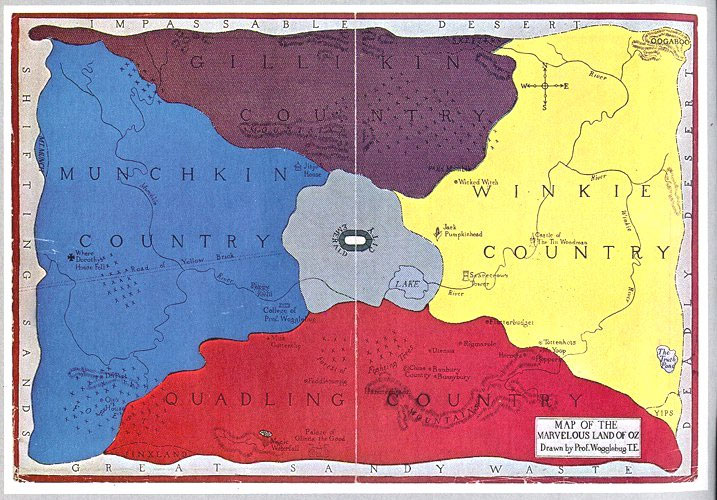

A company with a capital of $10,000,000 was organized in San Francisco in 1872 for the exploitation of a diamond field somewhere north of Fort Defiance in Northeastern Arizona. The reputed discoveries of the field were two miners named Arnold and Slack, who exhibited in New York and San Francisco some magnificent rough diamonds and some very good rubies. The San Francisco company included a number of the wealthiest men of the city, with significant mining experience. They sent out some agents who returned with more diamonds, picked up from the surface of the ground. Just the location of the find was disputed; however, for it was told that locations made north of Fort Defiance were merely for the purpose of diverting attention when in reality, the field where the diamonds had come from was south of the Moqui villages.

The whole scheme was a fraud on a gigantic scale. It was uncovered by Clarence King, the noted western geologist, who first demonstrated that the diamonds were not of the same character, bearing characteristics both of the South African and Brazilian fields. King visited the Arizona field and confirmed his own belief that it had been salted with stones brought from abroad. It is probable that the two “discoverers” were merely tools of much more wealthy men, who expected not only to get back the gems that had been “planted,” but to sell stock to the unwary small investor. There was another fake diamond “discovery” down on the Gila, not far from Yuma, but this was on a much smaller scale and excitement died even more quickly.

(Editors note: The Great Diamond Hoax was exposed on November 26, 1872, when the San Francisco Evening Bulletin published Clarence King’s findings. William Ralston, who formed the New York Mining and Commercial Company to invest in the reported Diamond Mine, had given $600,000 to Arnold and Slack but was never able to recover it. Arnold reported lived his few remaining years in Kentucky, and Slack blew his money in New Mexico).

A Basket Soon Emptied

One of the many short-lived boom camps of Arizona was Quijotoa, located 65 miles west of Tucson, by the side of a mountain shaped like a basket. The name came from the Papago word, “kiho,” meaning basket. The first mining locations were made early in 1879 at the bottom of the hill, renamed Ben Nevis by a man named Alexander McKay, one of the pioneers of the boom camp. On May 11, 1883, Charles Horn or Alexander McKay discovered rich croppings at the summit of the hill and then the excitement began. It was claimed that five tons of the ore gave a return of .$2,500 at the Benson smelter. Tunnels were started into the hillside to cut the ledge at depth but failed, for there was no ledge. In the language of a San Francisco mining man, the deposit was ”merely a scab on top of the mountain.”

McKay gave a bond on the property to the Flood-Fair-Mackey-0’Brien syndicate of San Francisco at a price of $150,000, but the option was not taken up at maturity. A half-dozen companies were formed in San Francisco, each with ten million dollars capitalization, for the working of the Quijotoa mines, and the news broadcasted that Arizona had found another Comstock Lode. As a result, thousands of men flocked in, despite warnings that the mines were only in the development stage. Around the original Logan townsite was four or five additions. In January 1884, at Quijotoa, were only a couple of tents, ten miles from water. Two months later, several thousand people had come and there were many marks of a permanent town, including a weekly newspaper, “The Prospector,” published by Harry Brook. The time the boom broke is indicated best by the fact that the printing office was moved to Tucson in the fall of 1884. Soon thereafter, J. G. Hilzinger of Tucson bought the mines, a mill that had been moved over from Harshaw, and all the other property of the principal corporation for $3,000.

Written by James Harvey McClintock in 1913, compiled and edited b Kathy Weiser – Legends of America, updated December 2019.

Notes and Author: This article is primarily a tale told by James Harvey McClintock between the years of 1913 and 1916 when he published a three-volume history of Arizona called Arizona: The Youngest State. However, the article that appears here is far from verbatim. While the story remains essentially the same as originally published, heavy editing has occurred for spelling and grammar corrections, revisions for the modern reader, and updates to this historic tale. McClintock began his career working at the Salt River Herald (later known as the Arizona Republic). He later earned a teaching certificate, served as Theodore Roosevelt’s right-hand-man in the Rough Riders, and become an Arizona State Representative. He died in California on May 10, 1934, at the age of 70.